Mapping the Communication Problem in Cyber Security

Mapping the Communication Problem in Cyber Security

Over the next few blogs posts, I’ll be posting some Wardley maps that I’ve been working on.

My original goal and starting point was to use 2 maps as input, in oder to think about some of the problems that is currently affecting the Infosec industry in my opinion, and map out potential solutions to address them.

The maps I used as input were the following:

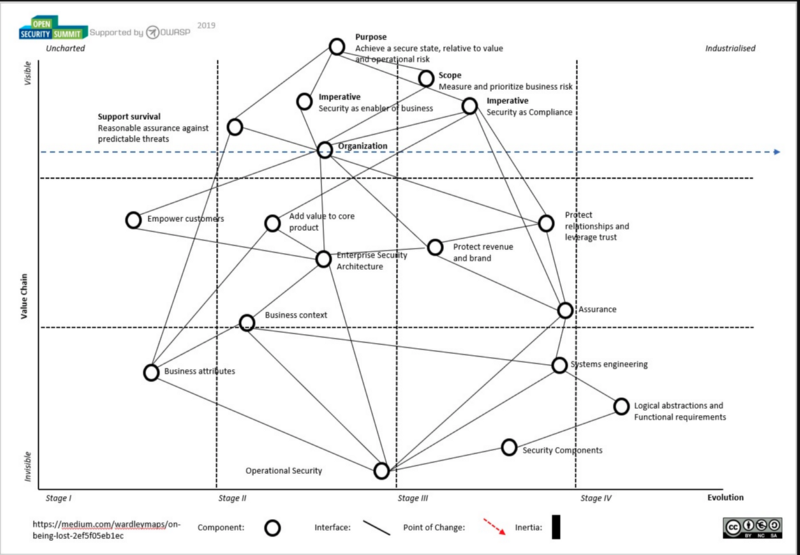

Map of security mapping I created and reviewed with other security professionals at the Open Security Summit 2019 which you can find here (where I had the pleasure of getting commentary from swardley himself):

And also Michael Brunton-Spall map in https://github.com/devsecops/wardley-maps. A lot of this content also aligns heavily with Sounil Yu talk in RSA 2017 entitled “Solving Cyber Security in the next 5 years” which you can find here

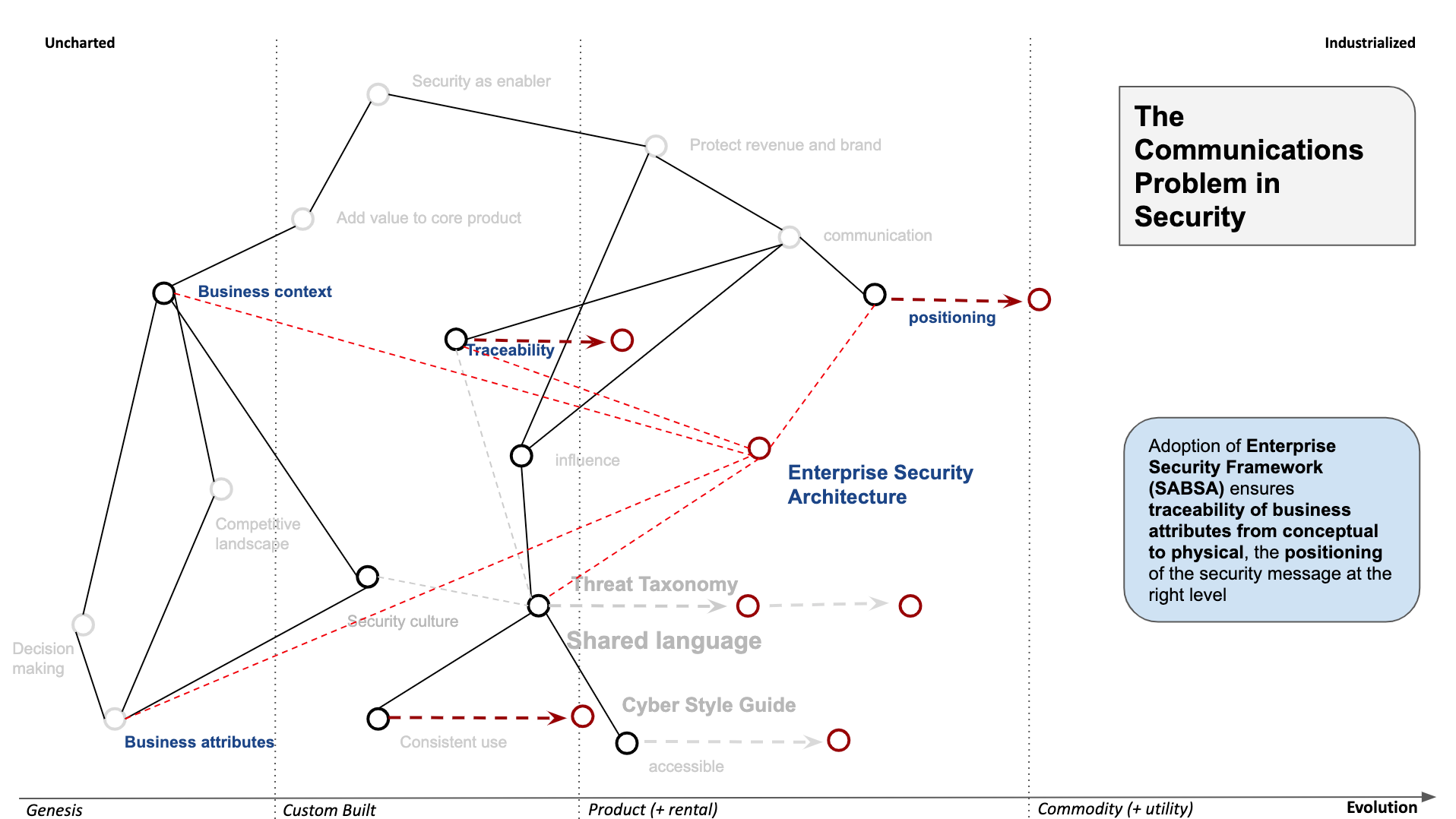

I’m making an hypothesis that there are 4 different problems that the Infosec industry needs to deal with if we’ll be successful into the 2020s, the first one of those being what I’m calling “The Communications problem”, and in order to map it, I started drilling down into sub-maps of the map of mapping.

This is the original version, for a brief explanation of what’s there. For those familiar with Wardley mapping concepts, you’ll see a lot of my proposals are around Doctrine of “adopt common language” which is absolutely critical for everything else.

Adding value to core product

Most of us, security professionals, we communicate with the goal of making security some which enables, as opposed to constrain, our organisations. We want security to be an enabler, and not a Compliance-oriented box ticking exercise.

If we’re going to aim for that, we need to ensure our activities are adding value to the core product, but also helping the organisation protect revenue and brand. Adding value to the core product, needs a security team which understands the business context that security and security transformation has, and I suggest those are made up of 3 key things to me:

- Competitive landscape

If we’re going to be proposing ways to improve our security posture, which comes at a cost to the organisation, we need to have at least a general understanding of what our competitors do about their security transformation and programmes. This is important for a few different reasons. First, it allows one to assess if our proposals and overall spend is in line with the competition, and that can be an important indicator for due diligence purposes (ie we give our organisation ability to evidence they are concerned about cyber security and allocate resources accordingly) and secondly it allows the CISO to position his programme as appropriate and in-line with industry as most board’s want to ensure their security is appropriate and provides the business assurances they require.

- Security culture

With this, I means “how secure are staff’s behaviours?” and “what are employees experiences with the security team?”. Do they embrace security transformation, and generally happy with measures implemented as they seem them necessary ? or does security have a bad reputation and people tend to avoid any direct engagement if they can avoid it ? These are all aspects that will affect how we communicate and get engagement, and not knowing or having the right strategy to move security communication forward, it becomes difficult get significant improvements.

- Decision making

The CISO needs to understand both the formal and informal power structures in the organisation, as if the messages are brought and positioned to the right people in the appropriate context, we’ll be more likely to influence decision making by the leadership teams and get the security budget and change we wish to do to help our organisation better manage cyber risk.

These components are all important, and all boil down to a number conscious or unconscious business attributes we’re aiming to adhere or attain, such as “resilient”, “monitored”, “confidential”, “compliant”.

Protecting revenue and brand

There are certainly other elements for effective protection of revenue and brand, but this map focuses on communication. In helping our organisations manage Cyber Risk, we should always bear in mind that Security is competing for resources and attention with all other areas of the organisation (Legal, Operations, IT) and that there’s limited resources for investment, so we should focus on establishing comparable terms to the other risk activities.

Remembering that a key aspect of our job in 2019 (some can argue, but this is how I like to view my work too) is to help “keep our directors out of jail”. What I mean by this, is that we need to ensure records exist of the different options presented and work with the business to find appropriate ways to reduce risk in a cost effective way, and that those options can later be reviewed to evidence the due diligence performed. This means we need to find an effective and scalable way of ensure a good portion of our communications are traceable and retained for future use as evidence if required.

Communication is also about positioning. For instance, both the CEO and the Developer will have to understand what they should do about “Supplier assurance” or “Supplier Security”, but they’ll have radically different views on what that means to them and what good security is for each of the domains, so our positioning of the message needs to be relevant and clear to audience if it’s to influence our stakeholders and drive engagement.

But in order to influence, having a shared language makes communication so much easier, and this is typically really difficult to achieve in security for a number of reasons:

- Different expertises within the security team — the Risk Manager rarely talks Security with the same terms as the Threat Hunter, so even within the security teams we use different names for similar things

- Different expertises throughout the organisation — if the security teams uses interchangeable terms in an inconsistent way, it gets harder for the security team to establish shared vocabulary that can be used to promote shared understanding of security issues. The use of jargon is also detrimental, as over time people will tend to not pay attention if they can’t understand what we’re on about.

So they key to enact positive change through communication across the organisation is to aim for establishing a shared language which is used consistently and is also accessible throughout the organisation.

So what can we do to improve this landscape ?

Improving the landscape

Using maps, I’m proposing 3 different activities we can use cumulatively or individually to start improving on this scenario.

Threat Taxonomy as a Categorisation system

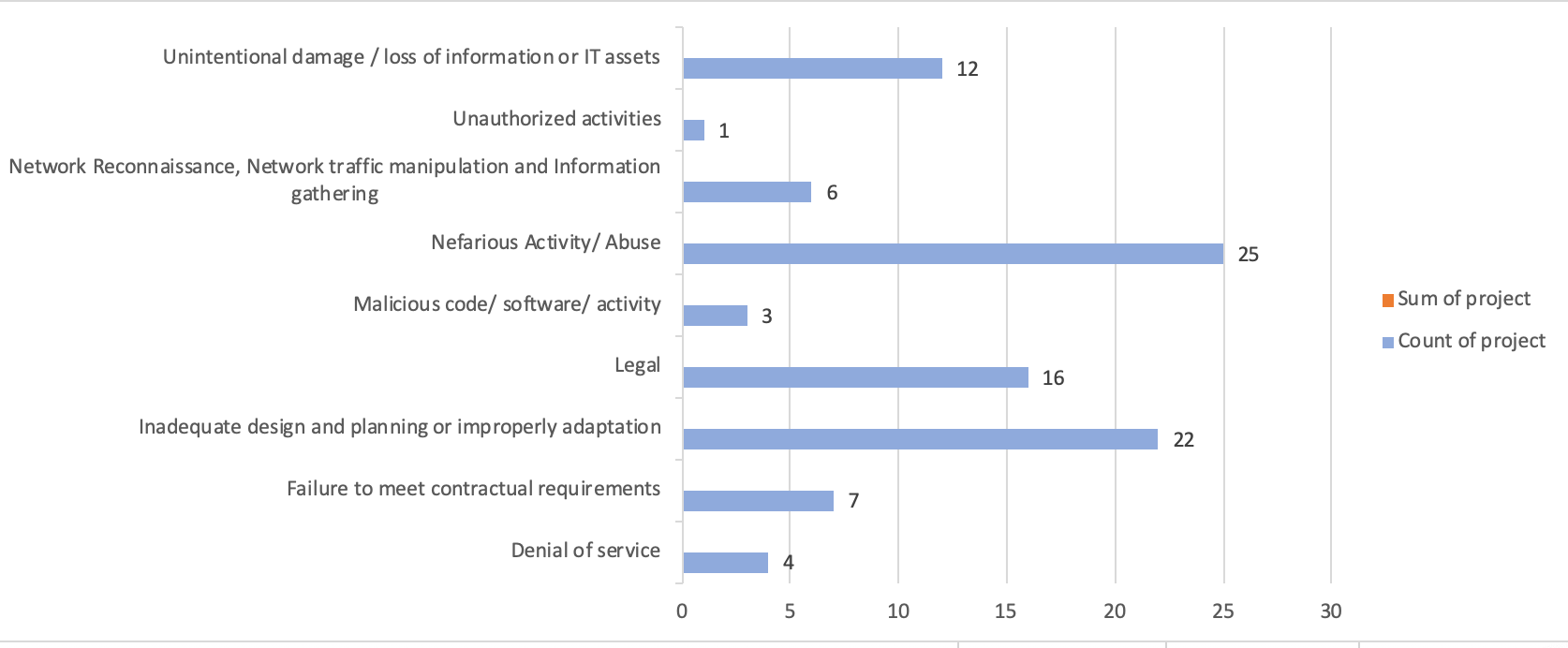

I almost implemented this at one of my clients, but the contract ended before we had the chance, but the main idea is that one can use a common Threat Taxonomy to use as the “glue” in communication across the organisation and give everyone a shared vocabulary in which they can summarise their concerns or we can summarise to them what our concerns are. I was told just a few hours ago there’s actual research on this which can be found here (as with most things security, sometimes you think you’re being smart but someone’s already done that for you :)). You can find the research here: https://www.sans.org/reading-room/whitepapers/threatintelligence/evaluation-comprehensive-taxonomies-information-technology-threats-38360

Whilst I agree with the author that there are no great options right now, as all taxonomies have different biases and pros/cons of attempting to use them as categorisation, I personally found that using a subset of ENISA’s might be a good enough approach. This is an example of what it could look like, through using metadata. I used a redacted ENISA’s Threat Taxonomy approach, taking away what’s not applicable to the organisation or would generally not be applicable so we could start with a smaller set of categories.

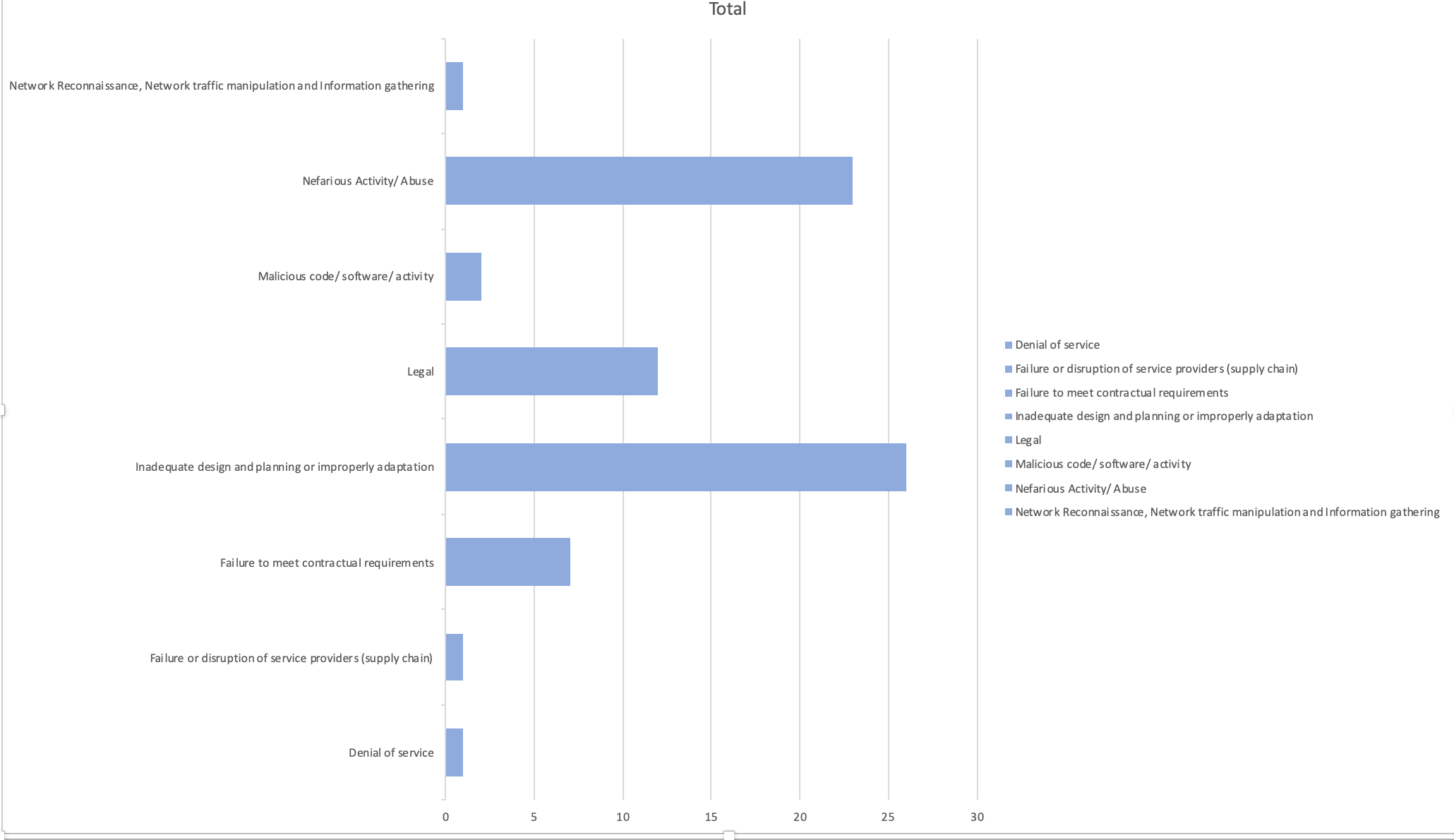

This could also be used to make it even more pervasive, by categorisation the projects we plan to implement and the services our teams provide with the same categorisation, so we can then enable traceability between a) what’s happening against b) what we’re spending our resources addressing.

Security projects categorised by Threats

Security services provided by CISO categorised by Threats they help mitigate

I believe that adopting Threat Taxonomy as metadata across org allows business context to be mapped and enables traceability through threats, incidents, vulnerabilities and risks but also projects and services provided or performed by the security teams, and can serve as a communication baselines for all dealings with the business. Culture is also influenced by shared language

Adopting a Cyber Security Style guide

Another one of the challenges communicating, is our collective ability to communicate complex problems back to management and other employees, in a way that ensures comprehension and drives action.

We don’t always make it easier on ourselves, particularly across different security teams as most pay little attention to the actual words we use. We may use different words when meaning the same thing making it difficult for our stakeholders to extend their vocabulary and associate or assimilate information over time.

For instance, if we’re talking about a new vulnerability which was recently identified, instead of calling it “zero-day” or “oh-day”, we should align in using “previously undisclosed vulnerability” when discussing it with the organisation.

There’s a brilliant publication by Bishop Fox called “Bishop Fox Cyber Security Style Guide”, originally meant for researchers but I believe it has a lot of potential outside research in that it can help us normalise our use of language across in a way that is consistent and business-driven. The more we can share language, the better we will communicate.

Adopting an Enterprise Security Architecture Framework

I have mentioned that one of the challenges with adding value to the core product, is understanding the business context and types of business attributes are being pursued. Unfortunately, we as an industry spend too much time with adopting best practices or fulfilling perceived compliance requirements, and we tend to do this following our “preferred standard” which will vary wildly depending our backgrounds.

People from a technical background tend to appreciate more technical standards like NIST, and the management or compliance ones tend to like COBIT or ISO 27001 as they’re more related to the management system. Also, the view of frameworks isn’t typically holistic, by focusing more on controls and less on enablement of our organisations.

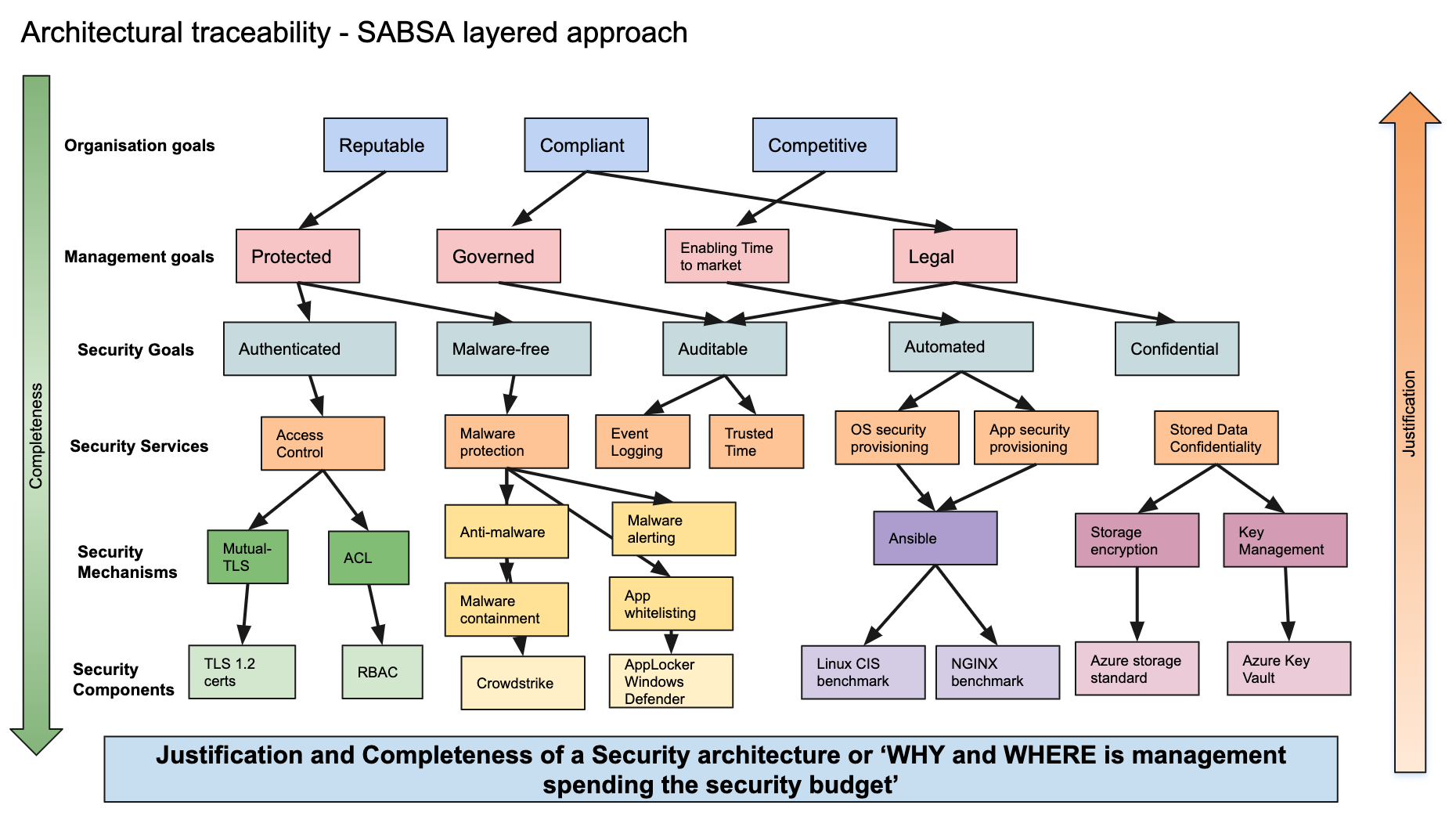

Another issue is that of traceability and positioning of the message, as security is much more than a few words on a policy and having assurance that the teams are focusing on the right problems and what we have vs what’s missing is becoming more and more important. We need to both be in a position to justify our spend requests whilst ensuring that our architecture is complete and pervasive to where it needs to be. In other words, we need to consider the consistency of our organisational design approach across a large complex system.

This is where a framework like SABSA can help fill that gap. I’ve wrote about it here previously

One of its main benefits is using SABSA as a communication mechanism, and open dialogue for discussion of options with stakeholders.

What I mean by this, is that instead of focusing on “you should implement this technology to achieve security goal X”, I can now engage in conversation with Engineers and Development teams as “There are these 3 mechanisms we should be using to assure business attribute Y. What’s the most efficient way to deploy a component to meet that requirement?

But if I’m talking with an Exec or Senior Manager, then I can focus the conversation to the level that matters to them, being very helpful to help position and trace the message we want to get across and how it’s helping he business with.

Strategically, it is also a great way to identify duplication and bias in the security mechanisms and components used, to ensure consolidation of components and operational overhead related with it.

Closing thoughts

We should be doing more to help our organisations improve their security posture, and that starts by focusing on our communication.

If we look at Wardley’s doctrine, these actions I propose in dealing and improving our communications would help address several aspects of Doctrine.

Use a common language — both facilitated by Cyber Style Guide and Threat Taxonomy as categorisation.

Be transparent — enabling full architecture traceability ensure we can be transparent across the organisation on what, why and where we need security to support business goals and not have security as something “that team does”

Remove bias and duplication — both in the use of language that is clear and unduplicated, but also by allowing traceability and understanding the mechanisms and components used, one can identify opportunities to reduce duplication too

All in all, I believe that the promise of DevOps was that we’d all be working together as a team, but I don’t think security as an industry is quite there yet but I have seen significant improvements over the last couple of years, also driven by people from different study and cultural backgrounds contributing, so let’s hope that continues and in this article I proposed 3 actions that can help you improve your own landscape.